Page 5 - Quadrivium

P. 5

QDV 6 (2015) ISSN 1989-8851 Identity, Dialogism and Liminality… Marcello Messina

Aspects of rituality

The identarian nature of the practice transforms it, in turn, into performance of identity, a ritual that van

Ginkel describes as intimately attached to blood and to the struggle of human versus animal, and to the

power, disgust and carnal fascination these elements evoke (2010:61-63). The notion of “ritual” associated to

the mattanza is recurrent in a lot of the literature on the subject (Torrente, 2002; Ravazza, 2010; Guggino,

2008). Among the other elements that compose the ritual, it is possible to list the prayers and all the other

manifestations of religious worship that accompany the practice (van Ginkel, 2010: 63; Torrente, 2002).

Among these manifestations, it is possible to mention the cialomi,6 the characteristic chants that accompany the

mattanza: these are a number of different traditional songs, all characterised by an antiphonic relationship

between a lead singer (cialumaturi), who initiates each verse, and the rest of the tunnaroti, who respond in

unison, in a strongly pronounced dialogic fashion. Importantly, the cialumaturi and the rais are not necessarily

the same person. Among the different cialomi, it is possible to mention Aiamola, which might be described as a

dialogic prayer, and Gnanzù, a more rhythmic song of both religious and secular content, normally sung just

before the most frenetic phase of the fishing; alongside these devotional chants, there are also obscene and

irreverent songs (Lina, Lina, Zzá Monica n cammisa), which usually make fun of the rais.

Liminality and dialogue

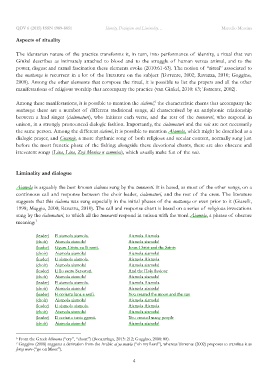

Aiamola is arguably the best-known cialoma sung by the tunnaroti. It is based, as most of the other songs, on a

continuous call and response between the choir leader, cialumaturi, and the rest of the crew. The literature

suggests that this cialoma was sung especially in the initial phases of the mattanza or even prior to it (Giarelli,

1998; Maggio, 2000; Ravazza, 2010). The call and response chant is based on a series of religious invocations

sung by the cialumaturi, to which all the tunnaroti respond in unison with the word Aiamola, a phrase of obscure

meaning:7

(leader) E aiamola aiamola. Aiamola Aiamola

(choir) Aiamola aiamola! Aiamola aiamola!

(leader) Ggesu Cristu cu lli santi. Jesus Christ and the Saints

(choir) Aiamola aiamola! Aiamola aiamola!

(leader) E aiamola aiamola. Aiamola Aiamola

(choir) Aiamola aiamola! Aiamola aiamola!

(leader) E llu santu Sarvaturi. And the Holy Saviour

(choir) Aiamola aiamola! Aiamola aiamola!

(leader) E aiamola aiamola. Aiamola Aiamola

(choir) Aiamola aiamola! Aiamola aiamola!

(leader) E ccriastu luna e ssuli. You created the moon and the sun

(choir) Aiamola aiamola! Aiamola aiamola!

(leader) E aiamola aiamola. Aiamola Aiamola

(choir) Aiamola aiamola! Aiamola aiamola!

(leader) E ccriastu tanta ggenti. You created many people

(choir) Aiamola aiamola! Aiamola aiamola!

6 From the Greek kéleusma (“cry”, “shout”) (Bonanzinga, 2013: 212; Guggino, 2008: 88).

7 Guggino (2008) suggests a derivation from the Arabic ai ya mawla (“oh my Lord”), whereas Torrente (2002) proposes to translate it as

forza moro (“go on Moor”).

4