Page 2 - mamm.73.3.169

P. 2

Article in press - uncorrected proof

170 M. Masseti: Homogenisation and the loss of biodiversity of mammals of the Mediterranean islands

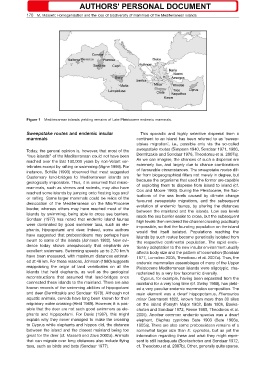

Figure 1 Mediterranean islands yielding remains of Late Pleistocene endemic mammals.

Sweepstake routes and endemic insular This sporadic and highly selective dispersal from a

mammals continent to an island has been referred to as ‘sweep-

stakes migration’, i.e., possible only via the so-called

Today, the general opinion is, however, that most of the sweepstake routes (Simpson 1940, Sondaar 1971, 1986,

‘‘true islands’’ of the Mediterranean could not have been Dermitzakis and Sondaar 1978, Theodorou et al. 2007a).

reached over the last 130,000 years by non-Volant ver- As we can imagine, the chances of such a dispersal are

tebrates except by rafting or swimming (Vigne 1999). For extremely low, and largely due to chance combinations

instance, Schu¨ le (1993) observed that most suggested of favourable circumstances. The sweepstake routes dif-

Quaternary land-bridges to Mediterranean islands are fer from biogeographical filters not merely in degree, but

geologically impossible. Thus, it is assumed that micro- because the organisms that used the former are capable

mammals, such as shrews and rodents, may also have of exploiting them to disperse from island to island (cf.

reached some islands by jumping onto floating logs and/ Cox and Moore 1993). During the Pleistocene, the fluc-

or rafting. Some larger mammals could be relics of the tuations of the sea levels caused by climate change

desiccation of the Mediterranean on the Mio/Pliocene favoured sweepstake migrations, and the subsequent

border, whereas others may have reached most of the evolution of endemic faunas, by altering the distances

islands by swimming, being able to cross sea barriers. between the mainland and the islands. Low sea levels

Sondaar (1977) has noted that endemic island faunas made the sea barrier easier to cross, but the subsequent

were dominated by good swimmer taxa, such as ele- high levels then rendered the channel crossing practically

phants, hippopotami and deer. Indeed, some authors impossible, so that the founding population on the island

have suggested that proboscideans may perhaps have would find itself isolated. Populations reaching the

swum to some of the islands (Johnson 1980). New evi- islands by such routes become genetically isolated from

dence today shows unequivocally that elephants are the respective continental population. The rapid evolu-

excellent swimmers. Swimming speeds up to 2.70 km/h tionary adaptation to the new insular environment usually

have been measured, with maximum distances estimat- affects body size and the pattern of locomotion (Sondaar

ed at 48 km. For these reasons, Johnson (1980) suggests 1977, Lomolino 2005, Theodorou et al. 2007a). Thus, the

reappraising the origin of land vertebrates on all the endemic mammalian assemblages of many of the Upper

islands that held elephants, as well as the geological Pleistocene Mediterranean islands were oligotypic, cha-

reconstructions that assumed that land-bridges once racterised by a very low taxonomic diversity.

connected these islands to the mainland. There are also

known records of the swimming abilities of hippopotami Cyprus, for example, having been separated from the

and deer (Dermitzakis and Sondaar 1978). Although not mainland for a very long time (cf. Swiny 1988), has yield-

aquatic animals, cervids have long been known for their ed a very peculiar endemic mammalian composition. The

migratory water crossing (Held 1989). However, it is pos- main element was a dwarf hippopotamus, Phanourios

sible that the deer are not such good swimmers as ele- minor Desmarest 1822, known from more than 30 sites

phants and hippopotami. For Davis (1987), this might on the island (Forsyth Major 1902, Bate 1906, Boeks-

explain why they never managed to make the crossing choten and Sondaar 1972, Reese 1995, Theodorou et al.

to Cyprus while elephants and hippos did, the distance 2005). Another common endemic species was a dwarf

between the island and the closest mainland being too elephant, Elephas cypriotes Bate 1903 (Bate 1903a,

great for the deer (cf. Masseti and Zava 2002a). Animals 1905a). There are also some proboscidean remains of a

that can migrate over long distances also include flying somewhat larger size than E. cypriotes, but as yet the

taxa, such as birds and bats (Sondaar 1977). information regarding these and what they might repre-

sent is still inadequate (Boekschoten and Sondaar 1972,

cf. Theodorou et al. 2007b). Other, generally quite sparse,