Page 6 - mamm.73.3.169

P. 6

Article in press - uncorrected proof

174 M. Masseti: Homogenisation and the loss of biodiversity of mammals of the Mediterranean islands

Figure 6 Third inferior molar of straight-tusked elephant, Ele- focused their speculation on the former existence in Mid-

phas (Palaeoloxodon) antiquus Falconer and Cautley 1847, dle-Pleistocene Sicily of a pygmy proboscidean, the ele-

reported from the island of Kalymnos, Dodecanese (Greece) phant of Falconer, Elephas falconeri Busk 1867, which

(courtesy of the 22nd Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical was only 0.90 m tall at the withers, with this being,

Antiquities, Rhodes). according to Roth (1992) and Lister (1993), the smallest

elephant that ever lived (Figure 8). A very abundant fossil

and phylogenetic affinities (cf. Raia and Meiri 2006). population (at least 104 specimens) of this species was

Dwarfism seems to be the only alternative large-sized recovered at the cave of Spinagallo, in eastern Sicily

animals have to lower selective pressure when they move (Ambrosetti 1968). Raia et al. (2003) computed the sur-

into insular settings (Mazza 2007). Most of all, the low vivorship curve for this fossil population in order to inves-

availability of resources sets insular populations under tigate both the great juvenile abundance and the high calf

the strict control of both genetic and ecological con- mortality revealed. Through the analysis of the survivor-

strains. Population densities are therefore confined ship of the elephant of Falconer, certain reconstructed

between a critical minimum number of individuals need- life-history traits, and its supposed ecology – and taking

ed to avoid extinction and a maximum number deter- into account the theory of ‘‘island rule’’ – they concluded

mined by the carrying capacity of the environment that E. falconeri veered somewhat towards the ‘fast’

(Mazza 2007). Recently, Raia et al. (2003) and Raia and extreme of the slow-fast continuum in life-history traits in

Meiri (2006) proposed a new explanation for the evolution comparison to its mainland ancestor, the straight-tusked

of body size in large insular mammals – and of elephants elephant, i.e., it was somehow r-selected. Thus, Raia et

in particular – using evidence from both living and fossil al. (2003) proposed a new explanation for the common

island faunal assemblages. They observed that the occurrence of dwarfism in large mammals living on

dimensional evolution of large mammals in different tro- islands: the interplay of competition, resource allocation

phic levels has different underlying mechanisms, result- shift and feeding niche width could successfully explain

ing in different patterns. Absolute body size may be only this pattern. Furthermore, Raia and Meiri (2006) sug-

an indirect predictor of size evolution, with ecological gested that the extent of dwarfism in ungulates depends

interactions playing a major role. Raia et al. (2003) on the existence of competitors and, only to a lesser

extent, on the presence of predators. According to Raia

and Meiri (2006), dwarfism in large herbivores is an out-

come of the increase in fitness resulting from the accel-

eration of reproduction in low-mortality environments.

In any case, I personally am of the opinion that we

should not undervalue the importance of the selection

exerted in relation to such specialisations by the principal

characteristics of the physical environment. If we pause

to reflect on the general appearance of the Mediterra-

nean islands in the Upper Pleistocene, or even only in

the Early Holocene, we realise how incommensurably dif-

ferent it was from that of today. In fact, there is possibly

no other place in the world which has been so intensively

influenced by human activity over a prolonged period as

the Mediterranean. Civilisations have been continuously

present for over 10,000–12,000 years, modifying entire

landscapes, disrupting or destroying the majority of

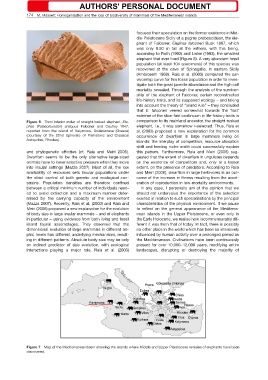

Figure 7 Map of the Mediterranean basin showing the islands where Middle and Upper Pleistocene remains of elephants have been

discovered.