Page 23 - mamm.73.3.169

P. 23

Article in press - uncorrected proof

M. Masseti: Homogenisation and the loss of biodiversity of mammals of the Mediterranean islands 191

avoided by keeping under control the self-referencing

aspect that often characterises certain genetic studies.

In any case, modern research is beginning to reveal that

the adoption of a multidisciplinary approach provides the

opportunity to advance intriguing hypotheses which may

prove particularly important in terms of the study, con-

servation and management of the extant Mediterranean

insular fauna (cf. Hajji et al. 2007, Masseti et al. 2008).

Another, and in no way secondary, aspect is the evalu-

ation of the anthropozoological and zooethnographical

importance of the ancient anthropochorous populations

of the Mediterranean islands.

The Rhodian deer. Concluding remarks

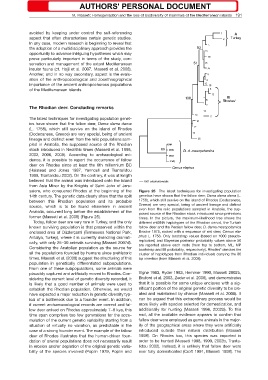

The latest techniques for investigating population genet- Figure 25 The latest techniques for investigating population

ics have shown that the fallow deer, Dama dama dama genetics have shown that the fallow deer, Dama dama dama (L.

(L. 1758), which still survive on the island of Rhodes 1758), which still survive on the island of Rhodes (Dodecanese,

(Dodecanese, Greece) are very special, being of ancient Greece) are very special, being of ancient lineage and distinct

lineage and distinct even from the relic populations sam- even from the relic populations sampled in Anatolia, the sup-

pled in Anatolia, the supposed source of the Rhodian posed source of the Rhodian stock introduced since prehistoric

stock introduced in Neolithic times (Masseti et al. 1996, times. In the picture, the maximum-likelihood tree shows the

2002, 2006, 2008). According to archaeological evi- different mtDNA haplotypes of the Rhodian cervid, the Turkish

dence, it is possible to report the occurrence of fallow fallow deer and the Persian fallow deer, D. dama mesopotamica

deer on Rhodes since at least the 6th millennium BC Brooke 1875, rooted with a sequence of red deer, Cervus ela-

(Halstead and Jones 1987, Yannouli and Trantalidou phus L. 1758. Only bootstrap values (based on 1000 pseudo-

1999, Trantalidou 2002). On the contrary, it was at length replicates) and Bayesian posterior probability values above 50

believed that the animal was introduced onto the island are reported above each node (from top to bottom, ML, MP

from Asia Minor by the Knights of Saint John of Jeru- bootstrap and BI probability, respectively). Rhodes* denotes the

salem, who conquered Rhodes at the beginning of the cluster of haplotypes from Rhodian individuals carrying the 80

14th century. The genetic data clearly show that the split bp insertion (from Masseti et al. 2008).

between this Rhodian population and its probable

source, which is to be found elsewhere in ancient Vigne 1983, Ryder 1983, Hemmer 1990, Masseti 2002b,

Anatolia, occurred long before the establishment of the Bruford et al. 2003, Zeder et al. 2006), and demonstrates

former (Masseti et al. 2008) (Figure 25). that it is possible for some unique enclaves with a sig-

nificant portion of the original genetic diversity to be cre-

Today, fallow deer are very rare in Turkey, and the only ated and maintained by chance (Masseti et al. 2008). It

known surviving population is that preserved within the can be argued that this extraordinary process would be

enclosed area of Du¨ zlerc¸ ami (Termessos National Park, more likely with species selected for domestication, and

Antalya, Turkey), where it is currently dwindling dramati- additionally for hunting (Masseti 1998, 2002b). To this

cally, with only 25–30 animals surviving (Masseti 2007d). end, all the available evidence appears to confirm that

Considering the Anatolian population as the source for fallow deer were employed as game animals in the major-

all the populations founded by humans since prehistoric ity of the geographical areas where they were artificially

times, Masseti et al. (2008) suggest the structuring of this introduced outside their natural distribution (Masseti

population in genetically differentiated subpopulations. 1998). On Rhodes too, this species was imported in

From one of these subpopulations, some animals were order to be hunted (Masseti 1998, 1999, 2002b, Tranta-

plausibly captured and artificially moved to Rhodes. Con- lidou 2002). Instead, it is unlikely that fallow deer were

sidering the current level of genetic diversity recorded, it ever fully domesticated (Croft 1991, Masseti 1998). The

is likely that a good number of animals were used to

establish the Rhodian population. Otherwise, we would

have expected a major reduction in genetic diversity typ-

ical of a bottleneck due to a founder event. In addition,

if current archaeozoological records are correct and fal-

low deer arrived on Rhodes approximately 7–8 kya, this

time span comprises too few generations for the accu-

mulation of the current genetic variability starting from a

situation of virtually no variation, as predictable in the

case of a strong founder event. The example of the fallow

deer of Rhodes illustrates that the human-driven foun-

dation of animal populations does not necessarily result

in erosion and/or depletion of the original genetic varia-

bility of the species involved (Poplin 1979, Poplin and