Page 3 - protected_areas

P. 3

www.nature.com/scientificreports/

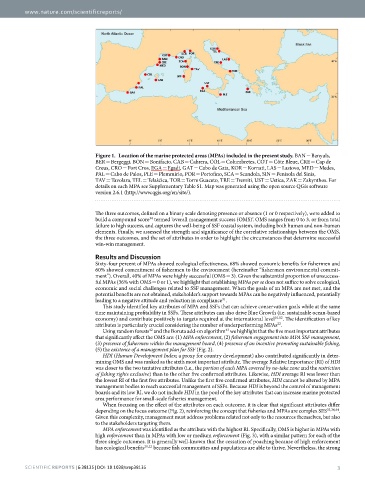

Figure 1. Location of the marine protected areas (MPAs) included in the present study. BAN = Banyuls,

BER = Bergeggi, BON = Bonifacio, CAB = Cabrera, COL = Columbretes, COT = Côte Bleue, CRE = Cap de

Creus, CRO = Port Cros, EGA = Egadi, GAT = Cabo de Gata, KOR = Kornati, LAS = Lastovo, MED = Medes,

PAL = Cabo de Palos, PLE = Plemmirio, POR = Portofino, SCA = Scandola, SIN = Penisola del Sinis,

TAV = Tavolara, TEL = Telašćica, TOR = Torre Guaceto, TRE = Tremiti, UST = Ustica, ZAK = Zakynthos. For

details on each MPA see Supplementary Table S1. Map was generated using the open source QGis software

version 2.6.1 (http://www.qgis.org/en/site/).

The three outcomes, defined on a binary scale denoting presence or absence (1 or 0 respectively), were added to

build a compound score termed ‘overall management success (OMS)’. OMS ranges from 0 to 3, or from total

34

failure to high success, and captures the well-being of SSF coastal system, including both human and non-human

elements. Finally, we assessed the strength and significance of the correlative relationships between the OMS,

the three outcomes, and the set of attributes in order to highlight the circumstances that determine successful

win-win management.

Results and Discussion

Sixty-four percent of MPAs showed ecological effectiveness, 68% showed economic benefits for fishermen and

60% showed commitment of fishermen to the environment (hereinafter “fishermen environmental commit-

ment”). Overall, 40% of MPAs were highly successful (OMS = 3). Given the substantial proportion of unsuccess-

ful MPAs (36% with OMS = 0 or 1), we highlight that establishing MPAs per se does not suffice to solve ecological,

economic and social challenges related to SSF management. When the goals of an MPA are not met, and the

potential benefits are not obtained, stakeholder’s support towards MPAs can be negatively influenced, potentially

31

leading to a negative attitude and reduction in compliance .

This study identified key attributes of MPA and SSFs that can achieve conservation goals while at the same

time maintaining profitability in SSFs. These attributes can also drive Blue Growth (i.e. sustainable ocean-based

economy) and contribute positively to targets required at the international level 10,12 . The identification of key

22

attributes is particularly crucial considering the number of underperforming MPAs .

Using random forests and the Boruta add-on algorithm we highlight that the five most important attributes

42

43

that significantly affect the OMS are: (1) MPA enforcement, (2) fishermen engagement into MPA SSF management,

(3) presence of fishermen within the management board, (4) presence of an incentive promoting sustainable fishing,

(5) the existence of a management plan for SSF (Fig. 2).

HDI (Human Development Index; a proxy for country development) also contributed significantly in deter-

mining OMS and was ranked as the sixth most important attribute. The average Relative Importance (RI) of HDI

was closer to the two tentative attributes (i.e., the portion of each MPA covered by no-take zone and the restriction

of fishing rights exclusive) than to the other five confirmed attributes. Likewise, HDI average RI was lower than

the lowest RI of the first five attributes. Unlike the first five confirmed attributes, HDI cannot be altered by MPA

management bodies to reach successful management of SSFs. Because HDI is beyond the control of management

boards and its low RI, we do not include HDI in the pool of the key attributes that can increase marine protected

area performance for small-scale fisheries management.

When focusing on the effect of the attributes on each outcome, it is clear that significant attributes differ

depending on the focus outcome (Fig. 2), reinforcing the concept that fisheries and MPAs are complex SES 33,34,44 .

Given this complexity, management must address problems related not only to the resources themselves, but also

to the stakeholders targeting them.

MPA enforcement was identified as the attribute with the highest RI. Specifically, OMS is higher in MPAs with

high enforcement than in MPAs with low or medium enforcement (Fig. 3), with a similar pattern for each of the

three single outcomes. It is generally well-known that the cessation of poaching because of high enforcement

has ecological benefits 21,22 because fish communities and populations are able to thrive. Nevertheless, the strong

Scientific RepoRts | 6:38135 | DOI: 10.1038/srep38135 3