Page 171 - KATE_JOHNSTON_2017

P. 171

(a passive capture method) is an ideal sampling method and provides historical data for

comparison to contemporary fluctuations (Addis et al. 2012, p. 134) – an argument I return to

in chapters five and six. Another problematic factor is the introduction in the late 1990s of

quota limiting the number of fish that would otherwise be caught, thus bringing into question

the usefulness of comparisons with previous data. The situation has been further complicated

by the difficulty in obtaining size composition of a large portion of the catch that are not

landed anymore but kept alive for fattening (ICCAT in Fromentin & Ravier 2005, p. 355).

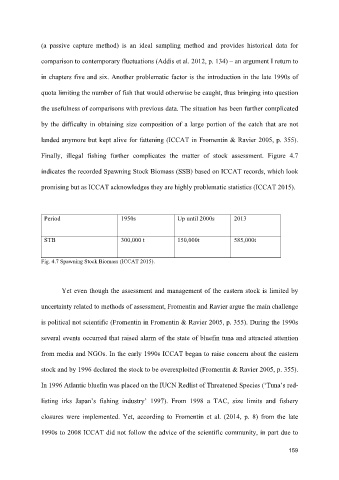

Finally, illegal fishing further complicates the matter of stock assessment. Figure 4.7

indicates the recorded Spawning Stock Biomass (SSB) based on ICCAT records, which look

promising but as ICCAT acknowledges they are highly problematic statistics (ICCAT 2015).

Period 1950s Up until 2000s 2013

STB 300,000 t 150,000t 585,000t

Fig. 4.7 Spawning Stock Biomass (ICCAT 2015).

Yet even though the assessment and management of the eastern stock is limited by

uncertainty related to methods of assessment, Fromentin and Ravier argue the main challenge

is political not scientific (Fromentin in Fromentin & Ravier 2005, p. 355). During the 1990s

several events occurred that raised alarm of the state of bluefin tuna and attracted attention

from media and NGOs. In the early 1990s ICCAT began to raise concern about the eastern

stock and by 1996 declared the stock to be overexploited (Fromentin & Ravier 2005, p. 355).

In 1996 Atlantic bluefin was placed on the IUCN Redlist of Threatened Species (‘Tuna’s red-

listing irks Japan’s fishing industry’ 1997). From 1998 a TAC, size limits and fishery

closures were implemented. Yet, according to Fromentin et al. (2014, p. 8) from the late

1990s to 2008 ICCAT did not follow the advice of the scientific community, in part due to

159